Understanding Spinal Cord Injury (SCI)

The science behind SCI

Understanding Spinal Cord Injury (SCI) is the first step toward navigating the journey of recovery and adaptation. This page, developed with insights from clinical experts, educators, and researchers, serves as your gateway to comprehending the intricacies of SCI. From detailed explorations of the spinal cord’s structure, the science behind understanding the type of SCI, the level of injury, to the complications common to SCI. We hope this acts as a resource for individuals and families navigating life after sustaining injury.

What is the spinal cord?

In order to understand SCI, first you have to look at the spinal cord itself.

The spinal cord is an extension of the central nervous system (CNS), which consists of the brain and spinal cord. The spinal cord begins at the bottom of the brain stem (at the area called the medulla oblongata) and ends in the lower back, as it tapers to form a cone called the conus medullaris.

The spinal cord is a thick bundle of nerves that runs through the vertebrae (backbones) in your spine. This nerve bundle is about 18 inches long, starting at the base of your brain and ending at your buttocks. The spinal cord acts as a superhighway between your brain and the rest of your body. Want to take a step, or wriggle a finger? The message is normally sent through the spinal cord to these body parts, in the form of nerve impulses. The highway runs in both directions: stub a toe or touch something sharp, and those pain or pressure signals speed back up along the spinal cord to your brain faster than you can say “ow.”

The spinal cord acts as a message highway between your brain and the rest of your body. It sends messages to the body to complete an action or function. It receives messages from the body and sends the information to the brain.

What is a spinal cord injury (SCI)?

Spinal cord injury or SCI occurs when trauma or illness damages the spinal cord. It results in partial or complete loss of movement, sensation (feeling) and function of organs like the bowel or bladder. Spinal cord injuries are classified as either traumatic or non-traumatic.

Traumatic Spinal Cord Injury (TSCI)

Defined as damage to the spinal cord resulting from an external physical force. This type of injury disrupts the cord’s normal function, potentially causing permanent changes in strength, sensation, and other bodily functions below the site of the injury. TSCIs can result from various incidents, including vehicle accidents, falls, sports injuries, and violence

Non-Traumatic Spinal Cord Injury (NTSCI)

Refers to damage or impairment to the spinal cord that is not caused by external physical trauma. Instead, NTSCIs can result from various non-traumatic factors such as diseases, infections, degeneration, or disorders that affect the spinal cord’s structure or function, leading to similar symptoms as traumatic injuries, like loss of mobility or sensation.The most likely causes of non-traumatic spinal cord injury are degenerative disc disease, surgical or medical complications, tumours, a stroke in the spinal cord, a neurological syndrome such as Transverse Myelitis, or an infection.

Complete vs. Incomplete SCI

There are two ways that experts organize the types of spinal cord injuries: By where in your spinal cord the injury happens (location) and the way the injury affects your spinal cord (complete vs. incomplete). An SCI can interrupt nerve signal traffic going to and coming from anywhere below where it happens.

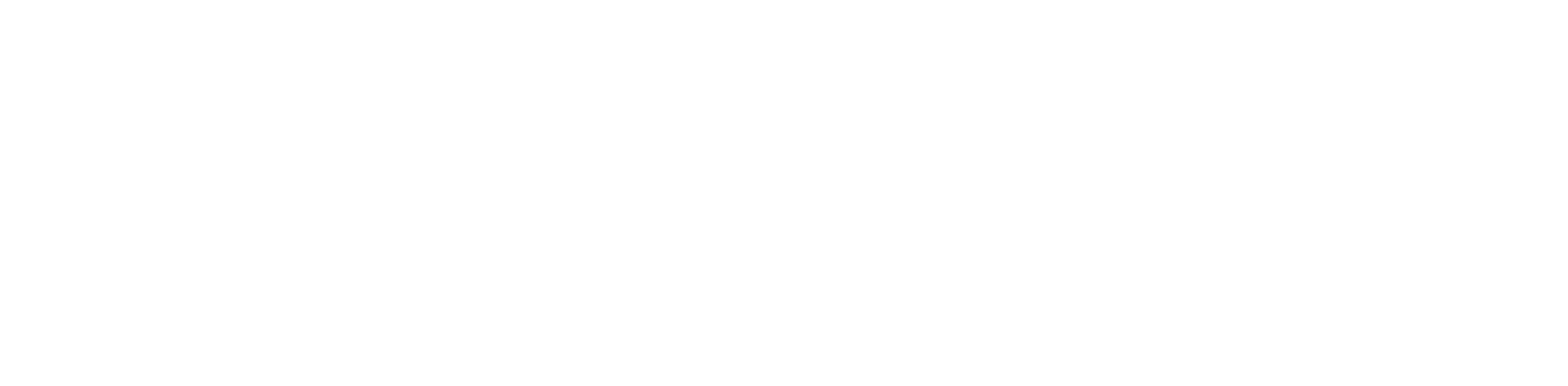

By location:

-

Cervical vertebrae (C1-C7):This section is in your neck. It goes from the bottom of your skull to about the same level as your shoulders.

-

Thoracic vertebrae (T1-T12):This section stretches from your upper back to just below your navel (belly button).

-

Lumbar vertebrae (L1-L5):This section is in your lower back. It extends about to the top of where your buttocks meet, but your spinal cord ends a couple of inches above that.

-

Sacral vertebrae (S1-S5):This section is in your pelvis.. It contains nerve roots below your butt to your tailbone.

By severity:

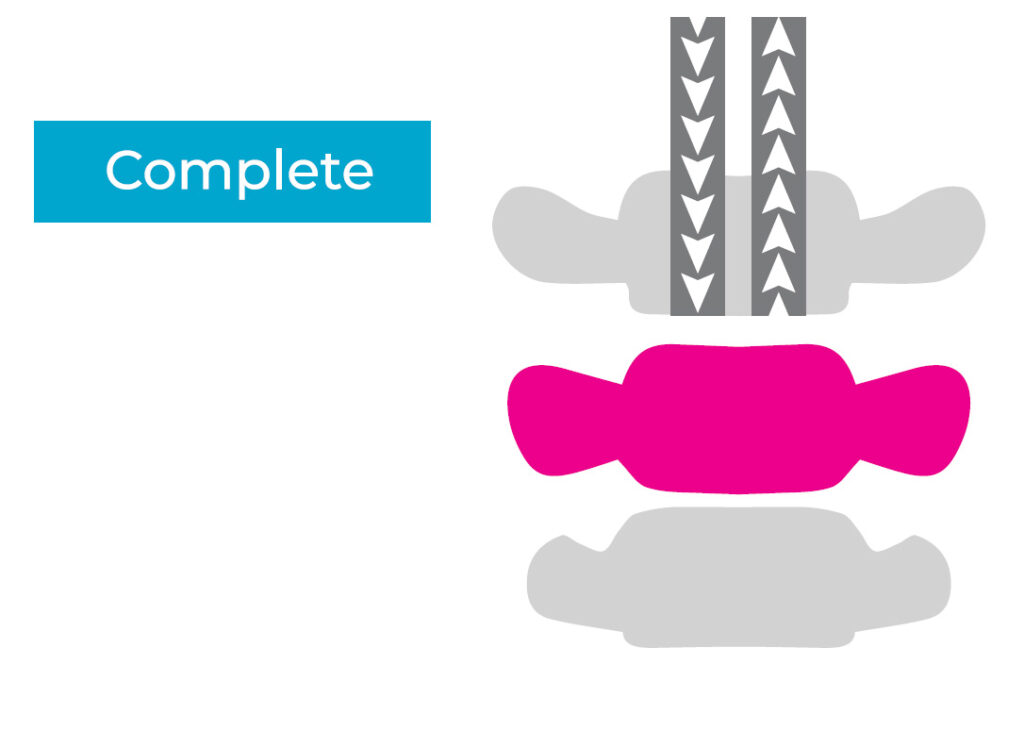

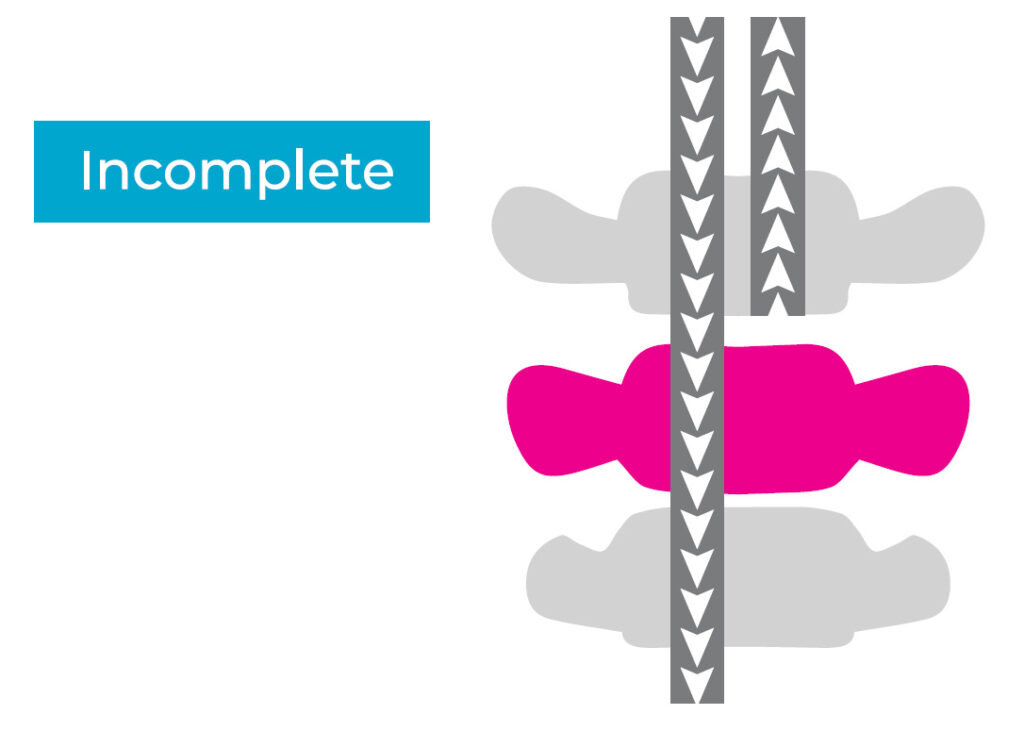

An SCI can either be complete or incomplete.

Spinal cord injuries are complete if the person has no voluntary movement or sensation below the level of injury. With an incomplete SCI, a person might have some feeling or movement below the level of injury. Or, one side of the body may have more function than the other.

In Ontario and Canada, the American Spinal Injury Association (ASIA) Impairment Scale is the standard tool used for classifying and defining SCIs. According to the ASIA , the clinical and research definitions are:

-

A complete SCI:Characterized by no preservation of motor and/or sensory function more than 3 segments below the neurological level of injury (NLI). This means that even a slight flicker of movement or a faint sensation in a single muscle below three spinal segments from the injury site indicates an incomplete SCI.

-

An incomplete spinal cord injury (SCI)Clinically defined as any damage to the spinal cord that preserves some function below the neurological level of the injury. This means that, unlike a complete SCI, there is some communication remaining between the brain and the body parts below the injury site. The degree and type of preserved function can vary significantly, making each individual’s experience unique.

-

Motor function:Some degree of voluntary muscle movement, even if limited or weak, below the injury level.

-

Sensory function:Some ability to feel touch, pain, temperature, or other sensations, even if diminished, below the injury level.

-

Autonomic nervous system function:This involuntary system controls functions like bowel and bladder control, sweating, and sexual function. Some individuals with incomplete SCIs may retain some level of control in these areas.

-

Neurological level of injury (NLI):This refers to the lowest level of the spinal cord where normal function is still present.

Sometimes an incomplete injury to the cervical spine is called Central Cord Syndrome. This is when the hands and arms have lost movement or sensation but the legs are less affected. So, a person with central cord syndrome might be able to walk but not really be able to use their hands. There have been advances in critical and acute care and early surgery to decompress the spine. Today, most people with a new SCI have an incomplete injury.

It’s important to note that incomplete SCIs can be incredibly diverse, and the specific type of injury can significantly impact an individual’s recovery and long-term prognosis. Consulting with a healthcare professional specializing in spinal cord injuries is crucial for obtaining a precise diagnosis and understanding the potential for recovery and rehabilitation.

Levels of SCI

The level of injury determines which parts of the body are affected. The higher the injury is on the spinal cord, the more body parts it will affect. For example: A cervical (neck level) injury will affect the upper and lower body. This is called quadriplegia or tetraplegia.

An injury to the thoracic spine (chest level) will affect parts of the trunk and lower body. This is called paraplegia. Lumbar and sacral injuries (lower spine) can also result in paraplegia.

Many people with spinal cord injury describe their injury in terms of the level. For instance, they might say, “I am a C5/6 quadriplegic.” That means that they injured their spinal cord at the level of the fifth and sixth cervical vertebrae.

The level of a person’s spinal cord injury affects the amount of movement and sensation they have below the level of injury. That in turn affects the types of activities they may need assistance with. For example, a person with an injury at the level of C4 may have movement in the neck and above, use a power wheelchair at home and in the community and direct their care for activities of daily living.

A person with an injury at the level of C7-8 may roll over and sit up in bed, transfer independently, perform most self-care, use a manual wheelchair in the community and drive with hand controls. These are general guidelines however, everyone is unique.

Why is the level of injury important?

The site of your injury will determine what parts of your body are paralyzed. The higher the injury, the more body parts that are affected. For instance, a spinal cord injury in the upper, or cervical, region of your spine will affect your arms as well as your trunk, legs and pelvic area (including bowel and bladder). Someone with this level of injury is considered to be quadriplegic. But an injury lower down, in the thoracic or lumbar region, won’t affect your arms. Someone with a spinal cord injury in either of these regions is considered to be paraplegic. About half of all people with SCI are quadriplegic, and half are paraplegic.

In some cases, you may assume someone is paraplegic, rather than quadriplegic, because they are using their arms and hands, but that may not be the case. Their injury could be in the upper, cervical region, and they may have some use of their arms and hands but it could be limited to varying degrees. This is good reason to never assume the degree of movement of someone you first meet – and, if it’s important to know, ask the person with an SCI for clarification.